A brightly colored Gasteracantha orb-weaver spider lives in the tropical savanna biome of Australia’s Top End (Northern Territory). Its glossy, shell-like abdomen is marked with bright green, red, and yellow hues, and it is armed with six stout red spines. Like other Gasteracantha species, it spins orb-shaped webs between trees and shrubs. Here’s a beautiful photograph posted to iNaturalist by zoologist @artanker (image CC-BY-NC):

Across the Gulf of Carpentaria, a similar spider can be found in the tropical savannas of the Cape York Peninsula (Far North Queensland). It shares some characteristics with the Top End spiders, but it has little or no green on its abdomen, and its spines seem to average a bit daintier. Here's an example from @coenobita (image CC-BY-NC):

These spiders are called Gasteracantha westringi(i) in Australia, but that name is incorrect, and the Australian populations may not have a valid name at all. This post will examine the situation and conclude with some questions that I hope researchers can pursue to sort out the situation. These orb-weavers are too spectacular to remain misidentified or nameless altogether.

Contemporary Literature and Photographs Posted Online

Trevor J. Hawkeswood’s 2003 book Spiders of Australia: An Introduction to their Classification, Biology and Distribution contains a color painting (plate 159) of a green, yellow, and red spiny spider labeled Gasteracantha westringi. It looks very similar to Arthur Anker's photograph from Darwin that I embedded at the top of this post. Hawkeswood's G. westringi species account says of the female, "abdomen greatly enlarged laterally, with three reddish to red-brown apical spines on each side; dorsal surface patterned with yellow, red and blue; this pattern is variable in shade and extent while the abdominal spines are often variable as well" (page 128). Hawkeswood lists the species' distribution as Queensland, Northern Territory, and Norfolk Island and says, "Nothing is known about the biology and behaviour of this most attractive and interesting species….”

Robert Whyte and Greg Anderson’s 2017 book A Field Guide to Spiders of Australia contains a photograph of a very similar green, red, and yellow orb-weaver from Darwin, which they label Gasteracantha westringii. “A gorgeous tropical spider most commonly found in the NT but also in QLD and Norfolk Island,” says the text. The book’s companion website, Arachne.org.au (where the species name is spelled G. westringi), features similar claims and photographs of similar individuals from Darwin, including a male individual, which as the authors note has not been formally described in the scientific literature: http://www.arachne.org.au/01_cms/details.asp?ID=2537.

The World Spider Catalog includes an entry for G. westringi (https://wsc.nmbe.ch/species/4080), listing a distribution of "Australia, Admiralty Is., New Caledonia.” The Australasian Arachnological Society’s checklist includes G. westringii on its 2020 checklist of Australian spiders: https://www.australasianarachnologicalsociety.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Australian-Spiders-1_42.pdf.

Many photographers and naturalists have shared images of these spiders on social media and personal websites, almost always from Darwin and surrounding areas. Here are some examples:

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/centralaustralia/5480981205/

- https://www.projectnoah.org/spottings/1857576004

- https://insectophilia.livejournal.com/158856.html

- https://ednieuw.home.xs4all.nl/australian/araneidae/araneidae.html

- https://www.tissaratnayeke.com/wildlife_spiders/h65FE1BEC#h65fe1bec

- https://www.facebook.com/shesgotlegsphotography/photos/a.718582354967419/1210319909126992/

Here are the observations of this form on iNaturalist: https://www.inaturalist.org/observations?place_id=any&subview=grid&verifiable=any&field:Gasteracanthine%20annotations=Unnamed%20Top%20End%20form.

As for Queensland, here’s an individual photographed from the Cape York Peninsula: https://www.flickr.com/photos/robertwhyte/35655497724/. These individuals are not frequently reported, though whether that’s a gap in reporting or a difference in abundance is unclear to me. This form does not seem to occur in the rainforests along Cape York’s east coast (the domain of G. quadrispinosa, G. fornicata, and G. sacerdotalis); rather, the reports come from the savannas and wetlands to the west, habitats more similar to those of the Top End.

Here are the observations of this form on iNaturalist: https://www.inaturalist.org/observations?place_id=any&subview=grid&verifiable=any&field:Gasteracanthine%20annotations=Unnamed%20Cape%20York%20form.

But Northern Australia’s Colorful Spiny Orb-weavers Are Not G. westringi(i)

Independent researcher @michael-gasteracantha, who probably knows the literature and status of Gasteracantha species as well as or better than anyone else in the world, has discovered that the popular understanding of northern Australia’s brightly colored Gasteracantha species is incorrect.

To understand why, we have to dig into the original 19th-century scientific literature — much of it in French and German — when many of the Gasteracantha species in Asia, Australia, and the South Pacific were first described and named (during a period of discovery, yes, but also of colonization and subjugation of lands and peoples).

When we do, we will find that G. westringi(i) refers to a species of New Caledonia and Norfolk Island, and the colorful forms of northern Australia's savannas do not appear to have a published name or names.

Although Gasteracantha species are colorful, charismatic, frequently encountered species distributed in tropical and subtropical environments all around the globe, often living in close proximity to humans, their taxonomy is still poorly resolved. Tan et. al summarized the primary reasons for this in a 2019 examination of several Southeast Asian species: “[T]he taxonomy of these spiny orb-weavers remain poorly understood due to the unavailability of male specimens in collections, poorly preserved type specimens, intraspecific morphological plasticity and the lack of distinctive morphological characters for a number of species in older descriptions….”

To their list of challenges, I would add that the bright colors of many Gasteracantha species can be lost or distorted when they are preserved as specimens, so 19th- and early 20th-century scientists who were working from specimens without having seen the species in life may have gotten the colors wrong (relative to living organisms) or ignored color patterns altogether in their descriptions.

By facilitating the sharing of photos from most places Gasteracantha species are found around the world, iNaturalist is helping shed light on long-running mysteries and challenge old assumptions because we can finally see in real time what these organisms look like and precisely where they are found. And the massive trove of literature available through World Spider Catalog (going back more than 250 years) lets us dig into the past and understand the history of scientific thought surrounding these fascinating organisms.

We start our exploration 157 years ago, when the name Gasteracantha westringii was first published.

Gasteracantha westringii as Described by Eugen von Keyserling

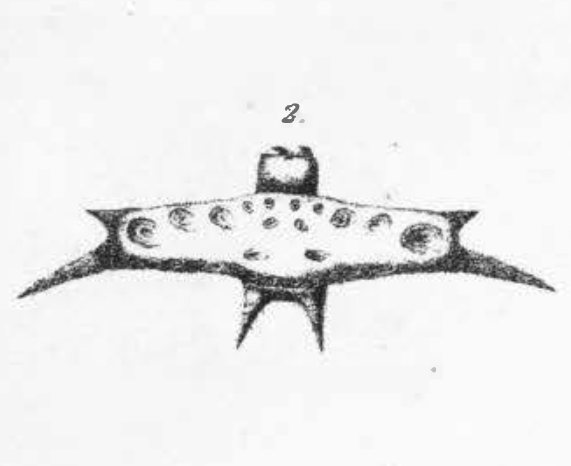

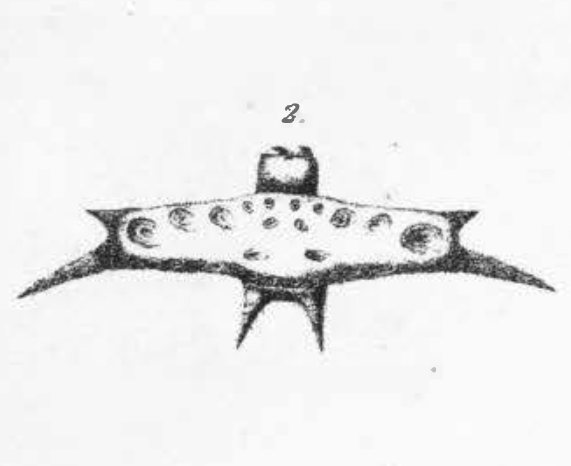

In 1864, arachnologist Eugen von Keyserling published a paper describing several “new and little-known” spider species, including a new species he named Gasteracantha westringii (presumably named for the Swedish scientist Niklas Westring, though Keyserling does not say so). That original paper may be downloaded here: https://wsc.nmbe.ch/reference/332.

Keyserling provided precise measurements of the specimen, a two-paragraph description, and an illustration. The cephalothorax was 3 mm long and 2.5 mm wide. The abdomen, without spines, was 4 mm long and 13 mm wide. The anterior spines were each 1 mm long; the median spines, 4.4 mm long; and the rear spines, 2 mm long.

Here is his description of the abdomen:

Das Abdomen ist etwas mehr als dreimal so breit wie lang, trägt jederseits an den Vorderecken einen kurzen, konischen, schwarzen Dorn und an den Hinterecken einen etwas nach hinten gekrümmten, der eben so lang wie das Abdomen breit ist und an der Basis schwarz, im übrigen Theil aber roth gefärbt erscheint. Am Hinterrande stehen zwei schwarze Dornen, die mehr als doppelt so lang sind als die der Vorderecken. Am Vorderrande zeigen sich zehn Narben, von denen die mittleren ganz klein und die äusseren gross sind. Der Hinterrand hat acht und die Mitte vier Narben. Der obere Theil des Abdomens ist hellgelb, die Narben aber sind schwarz. Der untere Theil ist schwarz mit gelben Flecken und Punkten.

Here’s a rough English translation with help from www.deepl.com/translator and Google Translate:

The abdomen is slightly more than three times as wide as it is long. The abdomen has a short, conical, black spine on each side at the front corner and slightly backward-curved spines at the rear corners. The latter spines are just as long as the abdomen and are black at the base, but the the rest of them appears red colored. At the rear edge, there are two black spines, which are more than twice as long as those on the front corners. There are ten sigilla at the front edge; the middle ones are very small and the outer ones large. The rear margin has eight, and the middle [of the dorsal abdomen] has four sigilla. The upper surface of the abdomen is light yellow, but the sigilla are black. The underside of the abdomen is black with yellow spots and dots.

Here’s his illustration:

Let’s compare that original description and illustration with contemporary Australian observations, like this one from @gposs (image CC-BY-NC-SA):

We can see that these orb-weavers do not match very well. The body of our Australian spider is certainly wider than long, but not by more than three times. The median spines are not as long as the body, and they are not curved backwards. The pattern of the sigilla looks similar, but the colors are wrong: all six spines are red, with no black base on the median spines, and the dorsal abdomen is significantly more colorful than the specimen described by Keyserling.

However, we know that Gasteracantha specimens do not hold their vibrant colors, and we know that there’s a lot of variability within species in this genus, so maybe this first description is just unusual. Keyserling was looking at only one specimen, after all ("Ein Exemplar in meiner Sammlung”).

Where did Keyserling’s specimen originate? And where is it today?

Those are both open questions. “Patria? (Homeland?)” he wrote of this species. Other species he described in the same paper, like G. thorelli, had descriptions like “Patria: Nossi-bé” (“Homeland: Nosy Be [Madagascar]”), but he did not know the origin of the specimen he named G. westringii.

And apparently, we do not know where this specimen is today. Is it in Tartu, Estonia, where he studied, or in St. Petersburg, where his specimens from Iran went? Is it in Vienna or London, or was it lost to time or war?

In taxonomy, the first valid use of a scientific name carries immense weight, so lack of clarity or loss of a type specimen can create a lot of problems.

Let’s keep going.

Gasteracantha laeta as Described by A. Fauvel

In 1865, the Bulletin de la Société Linnéenne de Normandie published Charles Adolphe Albert Fauvel’s description of a Gasteracantha species from New Caledonia (the first of its genus described from New Caledonia, he believed) based on two specimens collected in Noumea by a French Navy surgeon. That paper is available here: https://wsc.nmbe.ch/reference/338.

Fauvel named the species G. laeta. He provided descriptions in Latin and French, and a scientific illustration. From his French description:

Abdomen court, trois fois environ plus large que long, polygonal, relevé transversalement sur le disque; côté antérieur faiblement arrondi, postérieur visiblement arqué, prolongé en arrière en deux tubercules ou épines très-aiguës, de longueur médiocre; deux épines à chaque extrémité du côté supérieur, petites, noires, deux autres médianes robustes, un peu arquées en arrière, moitié plus longues que les postérieures, d'un rouge-orangé, noirâtres à la base et au sommet; en dessus, d'un jaune-orangé clair; côtés postérieurs, à partir des épines médianes, et prolongements inférieures d'un brun-rouge foncé; en avant, un série transverse de points ombiliqués, les médianes petits, les externes progressivement plus gros, noirs, cerclés obscurément de jaune pâle; sur le disque, au milieu, quatre autres points rapprochés, les inférieurs moitié plus grands, écartés; en avant du petit bourrelet inférieur, one autre série de neuf points, également ombiliqués et noirs, plus allongés et moins apparents. Ventre brilliant, en cône très-obtus, d'un rouge brique, marbré de jaunâtre; quatre à cinq sinus assez marqués; à la base ventrale, au-dessous de la vulve un petit tubercule épineux peu prononcé, noir.

And a rough English version:

Abdomen short, about three times as wide as long, polygonal, raised transversely on the disc; anterior edge slightly rounded and posterior edge visibly arched, prolonged behind into two very sharp tubercles or spines, of mediocre length; two spines at each end of the upper side, small, black, the other two robust median spines a little arched backwards, half again as long as the posterior ones, reddish-orange, blackish at the base and top; above, light yellow-orange; posterior sides, starting from the median spines, and lower extensions of a dark reddish-brown; in front, a transverse series of sigilla, the median ones small, the outer ones progressively larger, black, darkly circled with pale yellow; on the disc, in the middle, four other sigilla close together, the lower ones half as large, set apart; in front of the small lower rim, another series of nine points, also umbilical and black, more elongated and less conspicuous. Belly bright, cone-shaped, very obtuse, brick-red, marbled yellowish; four to five sinuses quite marked; at the base of the belly, below the epigyne, a small, black, spiny tuber, not very pronounced.

Fauvel described the species as measuring 9 mm long and 20-22 mm long, with the spines.

Here is his illustration:

The parallels between Fauvel’s New Caledonian G. laeta and Keyserling’s G. westringii of unknown origin are striking. The measurements match: Keyserling’s 3 mm long cephalothorax, 4 mm long abdomen, and 2 mm long backward-pointing posterior spines add up to Fauvel’s 9 mm total length; the same is true of the width measurements. Both descriptions focus on an abdomen three times long as wide, and strong, slightly backwards-curved median spines that are black at the base and red for most of their length. The sigilla patterns match too.

What do we find if we look at contemporary observations from New Caledonia? This stunning observation is from @damienbr (image CC-BY-NC):

Well now, how about that? Everything from Keyserling and Fauvel comes to life before our eyes! We’ll come back to this soon.

Gasteracantha westringii and G. mollusca as Described by L. Koch

In 1871 Ludwig Carl Christian Koch published the first part of his masterwork, Die Arachniden Australiens, which the Australasian Arachnological Society says "remains the benchmark literature on Australian arachnids” to this day.

In that 1871 volume (https://wsc.nmbe.ch/reference/421), Koch treated two species of interest to our case.

The first was Gasteracantha westringii. He referenced Keyserling’s description from a few years before. He mentioned two female specimens housed in Vienna’s Naturhistorisches Museum (though whether one of those was Keyserling’s original he does not say).

His two-page description has several elements in common both with Keyserling’s original description of G. westringii and Fauvel’s G. laeta (to be clear, though, Koch does not mention the latter). The abdomen, without the spines, is three times longer than wide. The median spines are relatively long and curve backwards; they are black at the base and what Koch describes as “brown” for the rest of their length (it’s clear from his description that the colors of the specimens he examined were badly faded, though he doesn’t seem to have known that). The posterior spines are longer than the short anterior spines. He notes something in his text that Keyserling (and to a lesser extent, Fauvel) illustrated but did not comment on, which is that the distance between the two posterior spines is relatively narrow, less than the length of one of the median spines.

Here is his illustration:

Let’s compare to another example of our colorful Top End species, this one from @tropicbreeze (image CC-BY-NC-ND):

Observe the placement of the posterior spines. They are widely spaced and angled, with the gap between them much wider than the length of a stout median spine, very unlike the narrower distance described and illustrated for G. westringii. And as we’ve already observed, those median spines are relatively short and straight (and do not have black at their bases).

Let’s look at another contemporary observation from New Caledonia, this one from @jakob (image CC-BY-NC):

It’s a match. Koch, Fauvel, and Keyserling all seem to be illustrating and describing this beautiful species.

Keyserling didn’t know where his specimen had come from; Fauvel knew his were from New Caledonia. What did Koch say about G. westringii?

Here’s where Koch apparently introduced 150 years of confusion: Of G. westringii, he wrote, “Vorkommen: Neuholland.” Occurrence: New Holland — an old term for Australia in both English and German. Those two words seem to have enshrined G. westringii in the Australian fauna, where — to skip ahead for a moment — the name somehow became attached to the colorful northern species we’re examining in this article, despite the fact that it does not match the early descriptions.

Why does Koch say “Neuholland,” and what does he mean by it? The term “Neuholland" was already something of an anachronism: The name “Australia” (“Australien” in German) had been in use for decades by 1871, and Koch used that more contemporary name often in his opus — including in its title. Elsewhere in the 1871 publication, Koch seems to indicate that “Neuholland" is a vague and general term, used when a more specific location is unknown. Immediately after stating “Vorkommen: Neuholland,” he wrote that two female specimens of G. westringii were well preserved in Vienna, but he did not make a connection between those two statements. Were the Vienna specimens labeled as having been collected in Neuholland? If so, was the claim reliable? If not, did Koch have another reason to believe the species he was describing occurred in Australia? If the term were rather vague, did it refer strictly to mainland Australia, or might it have referred to the general region, including surrounding islands, either in the mind of the collector or of Koch himself? (If the specimens are still in Vienna, perhaps some of those questions could be answered.)

In this 1871 paper, Koch also described and illustrated a species from Noumea, New Caledonia, that he called Gasteracatha mollusca. It was an odd specimen, and Koch theorized that it was an individual that had molted just before it was collected because the exoskeleton was thin and soft. If he was correct, this means it could have been an immature individual that was not fully developed.

Koch described an abdomen 2.75 times as wide as long with very short anterior spines, longer median spines that curved back, and posterior spines that were longer than the anterior spines with a relatively narrow gap between them. He did not describe color. The specimen was deposited in Vienna. This is his illustration:

(A sidebar on the name G. mollusca: In an 1886 installment of Die Arachniden Australiens, which was by then being carried on by Eugen von Keyserling on Koch's behalf, Keyserling applied the name G. mollusca to a species from the Solomon Islands, which he believed was the adult form of Koch's G. mollusca. British zoologist Reginald Innes Pocock corrected that hypothesis in 1898, when he described the Solomon Islands species as Gasteracantha signifer (today, G. signifera) and pointed out Keyserling's error: "Keyserling, I think, confounded two species together when he described what is here named G. signifer as the adult of G. mollusca. At all events, none of the specimens of signifer, whether young or old, that I have seen agree with the figure and description of the original G. mollusca; and in Keyserling's collection of spiders, one of the specimens labelled by him G. mollusca is a representative of a form very like G. signifer, while the others are referable to a species closely allied to G. westringii, Keyserling.")

The "Modern" G. westringii Concept of Friedrich Dahl

Forty-three years later, in 1914, German zoologist Friedrich Dahl published a review of the genus Gasteracantha based on an examination of the specimens housed at the Natural History Museum, Berlin, and a review of all the literature available to him at the time: "Die Gasteracanthen des Berliner Zoologischen Museums und deren geographische Verbreitung." To this day, no one has published something so comprehensive on this group of orb-weavers.

At the Berlin museum, Dahl had access to eight particular specimens that all matched one another and that he felt sure were a match for Keyserling's 1864 description of G. westringii ("Daß Keyserling dieselbe Art vor sich hatte, kann wohl als sicher gelten," or "That Keyserling had the same species in front of him can be considered certain.").

One of those specimens — if I am interpreting Dahl's notations correctly — was one of the same specimens on which Fauvel had based his description of G. laeta: "Gasteracantha laeta Fvl. type, Noumea" is how Dahl noted it. The other seven were labeled "Gasteracantha mollusca L. Koch, Südsee-Inseln," that is from the South Pacific islands (rather vague). Dahl still wasn't sure what to do about Koch's original G. mollusca description, but apparently other collectors had attached that name to specimens that Dahl felt matched G. westringii.

So, Dahl synonymized G. laeta with G. westringii and provisionally synonymized G. mollusca here as well, noting that more specimens were needed to clear up remaining questions. He appeared to take Koch at face value that his specimens of G. westringii had come from Australia, musing, "Ebenso wird noch in Frage kommen, ob die Exemplare von Neu-Hollaud konstant verschieden sind, wie es die Kochsclie Figur fast vermuten läßt." ("Also still in question will be whether the New Holland specimens are consistently different, as Koch's figure almost suggests.")

Dahl also provisionally lumped two other published names together into his Gasteracantha westringii species concept: G. ocillatum (described from Norfolk Island in 1889 as very similar to G. westringii, sensu Koch) and G. wogeonis. G. wogeonis was described in 1911 in a single sentence by Norwegian arachnologist Embrik Strand based on a single specimen from Vokeo (Wogeo) Island off the northern coast of New Guinea (East Sepik Province, Papua New Guinea). Although he didn't comment on it specifically, Dahl appears to have linked this novel name with G. westringii because Strand begins his single-sentence description with the words "Weicht von G. Westringi Keys...." ("Differs from G. westringi Keyserling..."). However, Strand went on to publish a longer description and illustration in 1915, and neither the description nor the illustration bear the faintest resemblance to G. westringii, sensu Keyserling, or Koch, or Dahl, so that's mostly a distraction for our purposes in this article. However, Strand's G. wogeonis material is deposited in Frankfurt and is listed in the World Spider Catalog as a syntype for G. westringi, which almost certainly needs to be corrected through a reanalysis of the specimens at some point: https://wsc.nmbe.ch/species/4080.

So, as far as we can tell, Dahl drew on 50 years of literature and several specimens he examined himself to name spiders like the one pictured below G. westringii, and he believed they occurred in New Caledonia, Norfolk Island, Australia, and a small island off the coast of Papua New Guinea. This picture by @jeanro (CC-BY-NC-ND):

When we look at where such animals are found today, we find them on New Caledonia and the Loyalty Islands and on Norfolk Island and Phillip Island -- none on mainland Australia at all: https://www.inaturalist.org/observations?place_id=any&subview=map&taxon_id=513299. Norfolk Island even put them on a postage stamp: http://biostamps.narod.ru/worldlist/norf/norf_2004_sp/norf_2004_sp.htm. By the way, I have frequently seen G. westringi in New Caledonia misidentified as G. rubrospinis, apparently because people saw the scientific name of the latter and assumed it was a reference to the bright red median spines of G. westringi, without doing any real research to investigate that hunch. G. rubrospinis is a very different spider, as a look at the original descriptions shows: https://wsc.nmbe.ch/species/4032. (I have not seen any contemporary records matching those descriptions from New Caledonia.)

So What *Are* Those Colorful Orb-weavers in Northern Australia?

As we have shown at some length, the name G. westringi(i) seems to belong rightfully to a species of wet forests in New Caledonia and Norfolk Island far to the east of the Australian continent. That species' appearance differs dramatically and consistently from the spiny orb-weavers found in northern Australia's monsoonal savannas.

We know that Gasteracantha species can exhibit incredible polymorphism (e.g., G. cancriformis in the Americas: https://peerj.com/articles/8976/), but the gaps in morphology and geography are huge in this case, without obvious transitional forms or clear opportunities for gene flow.

I think the evidence indicates that Koch was either wrong or was misunderstood when he said that G. westringii was found in "Neuholland." Indeed, even as early as 1898, French naturalist Eugène Simon wrote, "Il est à noter que la provenance du type de G. Westringi « Australie » est incertaine" ("It should be noted that the provenance of the G. westringi type 'Australia' is uncertain"), though he does not say why he believes this.

Furthermore, there do not appear to be any descriptions in older literature of the colorful green, red, and yellow savanna-dwelling spiny spiders of northern Australia. Perhaps collectors and authors encountered those spiders, went to the literature to look for a name, found G. westringii listed (thanks to Koch) as the only name that wasn't associated with one of the other known Gasteracantha species in Australia, and decided that must have been what Koch was talking about through some crude process of elimination or a hard squint at the original illustrations and descriptions.

Several museums in Australia hold specimens identified as G. westringi; Atlas of Living Australia lists them: https://biocache.ala.org.au/occurrences/search?q=lsid%3Aurn%3Alsid%3Abiodiversity.org.au%3Aafd.taxon%3A0dbffa86-a1b9-47e0-aa39-1270737b27df&fq=basis_of_record%3A%22PreservedSpecimen%22#tab_recordsView. However, none have photographs available online, so it's not possible to evaluate the identifications remotely. For the specimens collected in the Northern Territory and Queensland, how and why was the name G. westringi applied? Was it a faulty process of elimination or imprecise comparisons that just compounded across the decades? And what's going on with the alleged specimens from New South Wales and Bougainville? Those must be errors, surely.

Here are three hypotheses about who the northern Australian spiders might be:

Part of a Gasteracantha taeniata or G. diadesmia Complex

If we look west across the Timor Sea from Darwin to the dry forests of the Lesser Sunda islands (East and West Nusa Tenggara provinces of Indonesia and the independent nation Timor-Leste), we will find a population of spiky orb-weavers that looks a lot like the rainbow spiders of northern Australia, especially those from Queensland. Here's a photo taken by Heri Andri on the island of Sumba and shared on iNaturalist by @naufalurfi (photo CC-BY-NC):

Here are all the similar records on iNaturalist: https://www.inaturalist.org/observations?place_id=any&subview=grid&verifiable=any&field:gasteracanthine%20annotations=Unnamed%20Lesser%20Sundas%20form. These are labeled Gasteracantha taeniata on iNaturalist for now because we don't know what else to call them; they do not appear to have been described in the scientific literature either.

Like the Australian spiders, the Lesser Sundas individuals have variable patterns of red, yellow, and green on the dorsal abdomen and bright yellow spots on a dark venter. All six spines are red. And like the Queensland spiders, the Lesser Sunda spiders average less (or even no) green color on the abdomen, relative to the Darwin spiders, which tend to have very extensive green. Their abdomens are a little less angular than the Darwin spiders, and their median spines seem to average a little shorter and a little more slender and to curve back ever so slightly, as opposed to the thicker, straighter, longer spines on the Darwin animals.

There are iNaturalist records of this form as far west as Lombok, where the distribution appears to stop abruptly at the deep Lombok Strait, part of Wallace's Line, representing a break in species distributions between Indomalaya and Australasia.

Across the strait on Bali, and from Bali all the way to Northeast India, we find the Indomalayan Gasteracantha diadesmia, shown here in a photo from @naufalurfi (CC-BY-NC):

In G. diadesmia, the abdomen is more diamond shaped; the outer sigilla in the anterior row are smaller. There are two solid bands across the dorsal abdomen. But we see the reddish spines; yellow, red, and hints of green on the abdomen; and these spiders also have large yellow spots on their ventral sides.

Is there a kinship among all these spiders?

If we look north from Australia to New Guinea, we find black-and-yellow spiders in rainforest clearings of the foothills and the mountains; these are the typical Gasteracantha taeniata orb-weavers. Here is an image from @lizardview (CC-BY-NC):

The color patterns on the dorsal abdomen of New Guinean G. taeniata are very different from the Australian spiders we're discussing, but the shape and structure are conceivably within the realm of intraspecific variation based on variation observed in other species in the genus (again, consider the diversity of G. cancriformis forms in the Americas, where not only color and pattern but spine shape and even the number of spines varies widely).

Perhaps the colorful spiders of Darwin and the Top End are geographic variants of a widespread species in Australasia or Indomalaya, forms of G. taeniata or G. diadesmia, and they could be lumped with one of those species.

New, Undescribed Species

Another possibility is that together, or separately, the Northern Territory and Queensland (and Lesser Sundas) spiders are distinctive enough to warrant species status and would need a new name or names. Perhaps they've been isolated from their nearest neighbors on surrounding islands, or even from each other, for so long that they should be treated as unique. If this is the case, someone will have to prove it based on male and female morphology and probably genetic work, but the reward would be naming a one or more new species that have been right under our noses for generations.

Gasteracantha hebridisia

In several discussions here on iNaturalist, @michael-gasteracantha has pointed out that the Top End spiders bear a resemblance to a species described as Gasteracantha hebridisia from Aneityum, Vanuatu, in 1873 by A. G. Butler: https://wsc.nmbe.ch/reference/444. Butler described a spider with an abdomen about 2.5 times as wide as long and: "smooth, ochraceous, with four central and seventeen marginal reddish-pitchy impressed spots; spines purplish-black, rugose and pilose; ventral surface black, spotted with orange.... Somewhat intermediate in character between G. taeniata and G. Westringii, and remarkable for the unique colouring; of the ventral surface of the abdomen." (Of note, Aneityum less than 250 km from Maré, New Caledonia, where G. westringi(i) does occur today.)

In 1898, Eugène Simon recorded what he thought was G. hebridisia from Malekula, Vanuatu, noting the similarity of the specimens to Koch's description of G. westringii, too. He also described what he thought was a color variation of G. hebridisia from Vanikoro in the Solomon Islands, apparently a blackish animal with purple-red spines: "A typo differt abdomine et supra et subtus omnino nigro, acnleis Ieviter violaceo-tinctis" (in Latin, and good online translators don't exist).

Unfortunately, neither Butler nor Simon published illustrations of their specimens. Photographs from Vanuatu and the Solomon Islands are woefully lacking on iNaturalist and on other sites, so I have not found contemporary observations for comparison to these old written descriptions. Michael has seen the G. hebridisia material in the Natural History Museum in London and has said it bears striking similar to the Top End spiders. World Spider Catalog currently treats G. hebridisia as a synonym of G. taeniata, following Dahl (1914).

All this said, assuming the type location of G. hebridisia was accurately recorded, I struggle to see a biogeographic case for a spider occurring in southern Vanuatu and Darwin, Australia, with no obvious connections in between. Perhaps it's a case of convergence -- but with so little data from Melanesia, and relatively little study in northern Australia, we just don't know much for sure.

Research Questions for Discussion

I hope some who read this post will be inspired by the biological and taxonomic mysteries we've explored. Let's get these beautiful orb-weavers named properly!

Here are some questions that could be explored in a more formal research effort:

- What are the specific morphological and genetic characteristics of the Gasteracantha orb-weavers from Darwin and Cape York Peninsula that distinguish them from or unite them with other Gasteracantha species in the broader Australasian and Indomalayan realms?

- What became of Keyserling's original type specimen for G. westringii?

- Are one or both of Fauvel's type specimens for G. laeta at the natural history museum in Berlin?

- What information can be gleaned from Koch's G. westringii and G. mollusca specimens, if they are still extant in the Vienna museum?

- Can Koch's claim that his G. westringii material came from "Neuholland" be explained?

- What was Strand's G. wogeonis, really -- because from the description, it's unlike any of the forms discussed in this post.

- Depending on the outcome of a reexamination of Strand's G. wogeonis material, should that material be listed as a syntype for G. westringi(i), or not?

- Why does World Spider Catalog spell it G. westringi instead of G. westringii?

- Why does the World Spider Catalog list "Admiralty Is." as part of the range for G. westringi? Dahl provisionally synonymized Strand's G. wogeonis with G. westringii, and that specimen's source was Vokeo (Wogeo), an island in Papua New Guinea's Schouten Islands (not to be confused with Indonesia's Schouten Islands). PNG's Schouten Islands are near, but not the same as, PNG's Admiralty Islands. Is that be the source of the confusion? Or is there some other reference in the literature?

- Are there any descriptions or names for the "rainbow" spiders of the Top End and Cape York Peninsula lurking in the scientific literature? Have they really escaped formal description all this time?

- What are the specimens in Australian museum collections that are identified today as G. westringi(i)? How were they identified? Can they inform new taxonomic hypotheses for these spiders?

- Can studies on western hemisphere G. cancriformis inform studies in Australasia, or is the radiation in the Americas too recent to be comparable (or too different in some other way?

- What are we going to call these colorful Australian orb-weavers when we finally figure out their family tree?

Perhaps some of you know the answers to some of these questions, or have corrections or suggestions to the above. Let's discuss in the comments!

Tagging a few of you who may be interested: @twan3253 @tiwane @rfoster @matthew_connors @shesgotlegs @thebeachcomber @bushbandit @reiner @graham_winterflood @guillaume_delaitre @htct @cmcheatle @benkurek__ @ethmostigmus @ethan_yeoman